The Senses Succumb to the Sounds of Vietnam

Vietnam – Saigon & Hanoi: March 11 – April 5, 2017

We decided to spend the final month of our first year of nomadic travel in arguably what should have been the one place in South East Asia that we could have spent most of our time – Vietnam. Given that my wife is native-born Vietnamese we have fairly generous 5-year multi-entry visas. Yet for a variety of reasons, Vietnam was the final destination (rather than a natural home base) for our time in the region.

For starters, while the visas give us great access to the country, the current economics are not financially advantageous for traveling throughout SE Asia from Vietnam, as opposed to Thailand or Malaysia. But also, life in Vietnam (especially Ho Chi Minh City, its largest city) has a different pace and, for me, it’s something that can only be appreciated in short, quick bursts. That said, we decided to spend our final month or so visiting the two largest cities (Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi) after the hectic Lunar New Year period and before our eventual return to Europe in early April.

The Ho Chi Minh City Challenge

Ho Chi Minh City (or Saigon) can simply be described as “organized chaos.” It’s hectic, it’s hot, and it’s humid. While it’s not as hot and humid as Kuala Lumpur, at least in KL you’re typically indoors more or inside of air-conditioned public transportation. Not so much in Saigon. Life breathes outdoors in Saigon and at all hours of the day. It’s a city that never sleeps.

In our neighborhood in District 1, we would often hear Karaoke parties (with those notoriously loud and distorted speakers typical at any Vietnamese wedding) at 1-2 o’clock in the morning. Bicycle street vendors blaring their speakers at 2-3 o’clock in the morning as they rode down empty streets in their never-ending quest to sell bread, sandwiches, spring rolls, and soups. It was constant and inescapable. In some ways, it’s comforting (the energy, the ambience, the “city that never sleeps” feeling) but in other ways it was annoying, especially when you’re simply tired from the challenges of the day.

Challenge is perhaps the best word to describe this most recent experience for me in Saigon. Similar to our previous month in Malaysia, our first three weeks in Saigon were not adventure travel for us. We’d visited the city two years earlier on our belated honeymoon and saw many of the usual sights. This time it was all about work and study.

For the past year, I’d been studying Vietnamese on and off with private instructors in San Jose, California and online with a school in Saigon. My hope was to take my Vietnamese to the next level while living in country for a month. So, I decided to pursue intensive language instruction at the same school in Saigon with a private instructor – 2 hours per day, 3 days a week for 3 weeks. For at least three days a week I was focused on the language and the other 3 days I focused on my “day job.” Though it may sound like I had an additional day of rest, I’d soon to come to realize that simply being in Saigon doesn’t allow me to rest at all.

Learning How to Learn Differently

In a previous post titled “Thirsty – My Tongue’s Eternal Battle With a Knife,” I mentioned an experience during our time back in Verona, Italy last year when I was prompted to understand and then explain why travel and language learning is seemingly such torture for me. As I noted then “it may seem like torture but it’s a deep challenge,” and this could not have been more true of my 3 weeks in Saigon.

Every language presents its own set of challenges and each individual will wade through those challenges in different ways. Yet, while I knew that I needed to work on certain weaknesses within the language, I simply had no idea how much progress I hadn’t made in the previous year. Beyond the private instruction lessons (in-person and online) over the past year, I’d downloaded and studied about 100 podcasts (at both elementary and intermediate level). I’d begun writing travel recaps to my father in-law in Vietnamese and was praised for the quality of writing. However, after my first two private sessions in Saigon, it was clear that my way of learning the language needed to change.

Having learned Spanish and Italian to the level of conversational fluency, I adapted many of the same approaches to learning Vietnamese. Yet, I quickly found out that I would have to learn how to learn the language differently. The simple fact that Vietnamese is a tonal language completely changes how a non-native tonal language learner must go about learning the language. And I’ve found that trying to explain this to native tonal language speakers is difficult (if not, almost impossible). It’s of no fault of their own that they had never learned tones as an adult. Sponge-like learning as a child is vastly different than filtered-based learning as an adult. Unlike the southern romances languages that I’ve learned primarily through a comparison filter, Vietnamese is best learned without the filter and through a sponge.

Perhaps, I would have to sit down and write a completely separate post on the many intricate challenges and realizations that I experienced to fully capture my brief attempt at learning Vietnamese through intensive immersion. In lieu of that, I’ll simply share four key realizations that crystallized why the language and the learning experience presents such a different challenge for me. (If you’d rather skip this brief nerd-out on language learning, feel free to skip down to the next travel-related section of this post – Hitting the Depth of Despair).

—-Start of Nerd-Out—–

Learning to Speak in Tones from Native Speakers: As I alluded to earlier, native tonal language speakers learned how to speak in tones and differentiate changes in tones as children. It’s a skill that was learned and perfected long before they could consciously process how they were learning. Whereas, for those of us adults who now have to learn to both speak and hear tones, it is more of a cerebral process.

I’ve found that learning how to speak in tones is challenging when learning it from someone who never consciously learned that skill. I’ve had challenges with friends and family, as well as instructors. Their frustration at your inability to hear or speak a tone (something so simple and innate to them) can sometimes be counterproductive and debilitating. In my case, I primarily have trouble with 2 of the 6 tones in Vietnamese, although in some respects one of those “tones” is not a “tone” at all.

Understanding the Flat Doesn’t Mean Middle: The tone that presents the greatest trouble for me in Vietnamese is the flat tone. Throughout my studies prior to arriving in Vietnam, I’d always assumed that the flat tone was a middle tone. Being that I speak three other languages that do not have tones, I figured that if I simply mouthed words with flat tones in Vietnamese without any effort that I would naturally be speaking in a flat tone. I could not have been more wrong. I spent so much time trying to train myself to “find the middle” when speaking a word with a flat tone after having spoken a word in a higher or lower tone.

But finding the middle was such a challenge for me, primary because it was the wrong way to approach it. The flat tone is not a middle tone but rather it’s a high tone that is simply flat and long – and my natural voice is neither high nor flat. To my ear, when I speak this tone perfectly it sounds extremely weird. It almost sounds like I’m singing a word rather than speaking a word. So strangely, I can now hear when I speak a flat tone but it’s so unnatural in my style of speaking that instead of honing that sound, I shy away from it in normal speech.

Speaking and Reading Without Inflections: Vietnamese is perhaps the easiest language for non-natives to learn in the region simply because it is so literal. For the most part, every word sounds exactly how it’s spelled (with minor variations due to regional dialects). And what instructors tell you is that you speak in tones and not in inflections. Yet in languages without tones (e.g. English, Spanish, Italian), we use inflections…A LOT. We often don’t realize how much we use inflections until we have to learn how to stop doing it.

This was (and still is) a major hurdle for me in the language (especially since I’ve used inflections/pace to mask a natural speech impediment all of my life). I spent nearly the first 20 years of my life finding my voice in English and adapted the same approaches to Spanish and Italian. But I can’t learn to speak in the same way in Vietnamese. Instead, I have to change my natural pitch and pace to “hit the right notes” in Vietnamese. For if you don’t hit the right note, the listener will have a very difficult time understanding what you’re trying to say. In my limited opinion, I think this primarily because they understand sound before they understand words.

Having to Learn How to Spell at 3 Levels: Without getting too nerdy or complicated, it’s safe to say that Vietnamese is a monosyllabic language. For the most part, words are simply one (sometimes two syllables). But although the words are short, they are so very complex. It is perhaps that which makes Vietnamese easier to learn is also what makes it so challenging to break through.

Prior to French colonization in the late 1800s, Vietnamese as a written language resembled Chinese. It was written in characters and not letters. So it’s not surprising that as a spoken language, it’s a language of sounds and symbols, more so than words. The Romanization of Vietnamese may have made it easier for the imperialists to communicate within the culture but it also presents interesting wrinkles in learning how to process the language.

The best way that I’ve been able to describe this challenge is that learning words in Vietnamese requires me to learn every new word at 3 different levels. First, I have to learn it how I naturally do in English, Spanish, and Italian. I visually capture the consonants and the vowels and order them in the correct spelling. In my other languages, I would be done at this point but not in Vietnamese.

The second level requires that I figure out which version of the vowels to use because in Vietnamese there are 11 vowels – 3 (A’s), 2 (E’s), 1 (I), 3 (O’s), and 2 (U’s). Next, I then have to figure out which tone is being used in the word and there are six different tones to decipher – each of which express a completely different meaning.

So as you might imagine, attempting to commit new words to memory is quite the challenge and takes a much longer time than in Roman or Germanic languages. This doesn’t even take into account that some words require two syllables and you have to duplicate this process for the second syllable to simply remember how to express one thing.

As I studied the language more and more, and began to notice these nuances to the learning process, it became clearer to me that native speakers understand the language in a way that is fundamentally different than non-natives. This helps explain why many people can study Vietnamese in country for over a year or so and still feel like they struggle mightily with the language. So I guess I shouldn’t be so hard on myself after such a short period of time. Such is the story of my life.

—-End of Nerd-Out—–

Hitting the Depth of Despair

As I walked out the classroom after my fifth (of nine) sessions, I felt like I wanted to break down. I hadn’t walked more than 20 steps before I reached the stairs, walked another few steps down, and stopped. I almost couldn’t hold back the tears of frustration. I allowed myself this brief moment alone in the dark stairwell to allow the feelings to rush over me.

For as much progress as I thought I was making, I simply felt like I had absolutely no confidence in mouthing a word properly. Sure, the simple words that I knew, I could communicate. But as I began to grow beyond a few short words and phrases, it was becoming clearer that I did not (and still do not) have a command of the pronunciation of the language. I went from wanting to learn more and more words to feeling like a child unable to produce basic sounds. It was shattering. I’d reached a similar point twice before in my intensive Italian language studies but this time the feeling was different. It was deeper.

In Italian, I could speak but I was learning at a pace that needed to be calibrated – my mind simply needed rest to gather and organize all that I was learning. In Vietnamese, it seemed the harder I tried, the harder it became. Almost like the more you learn, the more you realize how much you don’t know. And for me, the issue was basic pronunciation. Meaning that if I didn’t have confidence in what I was saying or hearing, then it didn’t matter how many new words I tried to learn. I simply would not be able to commit them to memory if I couldn’t “see them in my mind.”

I took the next day off from Vietnamese, sort of. It’s hard when you’re living in country to take a day off. Everything you see, everything you hear is in the language. For weeks, I spent nearly every minute outside looking at signs and practicing pronunciation. But that Thursday I had to shut it off. I needed the break. I needed an escape.

Ironically, that Friday I stopped by one of my favorite banh mi sandwich street stalls on the hour-long walk to class. I started chatting it up with the husband of the banh mi vendor and we proceeded to have a Vietnamese/English “intercambio” – he spoke in broken English and I spoke in broken Vietnamese. After only a few exchanges, he complimented me on how well my Vietnamese sounded. I was shocked and confused.

Later prior to class, I met the owner of the language school and chatted with her in Vietnamese for a few minutes. She too commented on how well my Vietnamese sounded and again I was shocked and confused. Perhaps she was just providing good customer service and helping to build the confidence of a student that she could see was at a critical development point.

Regardless, it’s clear that I was able to converse with both people that day, understanding much of what they said and having them understand much of what I was saying. It helped build my confidence slightly, but then I returned to class and struggled, yet again, with speaking and hearing basic tones.

Patience is Truly a Virtue

For as chaotic and exhausting as Saigon is, the times we spent with my wife’s family were some of the most comforting and fulfilling. Her aunt and cousin live in District 3 (about a 20-minute walk from my school). So during our last week in Saigon, I’d walk over to their house after my class to first rest, then eat (amazing home cooked meals), and finally make attempts to converse with Aunt Ngoc.

Of all the people that I spoke with in Vietnamese during our brief time in country, Aunt Ngoc, was the most patient. She actively listened to me and really tried to understand what I was trying to say. She would make small corrections here and there but unlike others, she didn’t slam me every time I misspoke a tone. She seemed to intrinsically understand the power of teachable moments. She pointed out things around the house and said the Vietnamese words (even though it was very difficult for me to commit them to memory because, as a visual speaker, I still can’t “see” what I’m hearing).

She doesn’t speak too much English and so we patiently waded through conversations about coffee, travels, and family in Vietnamese. When learning a language, you need people like this around. People that will have patience when it takes you a minute to get through a basic sentence or that will point out minor tweaks rather than virtually slapping on the wrist or getting frustrated every time you make a mistake.

In addition to my afternoon chats with Aunt Ngoc, we spent every Saturday at her house exploring the neighborhood, eating her amazing meals, and taking long motorbike rides around town in the late evenings. Those moto rides were the highlight of our time in Saigon. Perhaps something that locals take for granted (the ability to just hop on a scooter and get around town) is the one thing that we enjoyed most during our trips. In the evenings the city sparkles, the energy increases, and yet the cool-air breeze from the back of motorbike makes it all so relaxing to explore.

We also enjoyed some quality family time with my wife’s uncle and his family each Sunday – again eating amazing food – and learning some random family history. Albeit, given the group size, I simply practiced listening (more than speaking) and received the actual conversational download once back at home with my wife.

Perhaps the next time we visit Saigon, we’ll stay in the calmer confines of District 3 rather than crazy chaos of District 1. Though I’ve had my struggles with the language, it’s not within my personality to give up. I’ll use these next few months to take a break, enjoy the comfort of speaking Spanish and Italian, and then recommitting later in the year to make another attempt at Vietnamese. That said, our trip up to Hanoi was a welcomed rest for my body and my brain, and surprisingly, a beautiful way to say goodbye to Vietnam this second time around.

Hanoi: From Chaos to Calm Comfort

Prior to our visit to Hanoi, there was a certain amount of anxiety and trepidation about visiting the government capital. My wife’s family is mostly from the South and after fighting in the war, her dad was captured soon after the Saigon fell in 1975 and sent to a “reeducation camp” for 7 years. The split between North and South is still strong in the country, especially for those who lost so much after the war. So visiting the city at the seat of the government that imprisoned your father is an emotional experience. In addition, through gossip from family and friends we’d been warned about speaking in the Southern dialect up North and how people in the North were unfriendly to their southern neighbors. As we quickly learned, as travelers, our experience was much different.

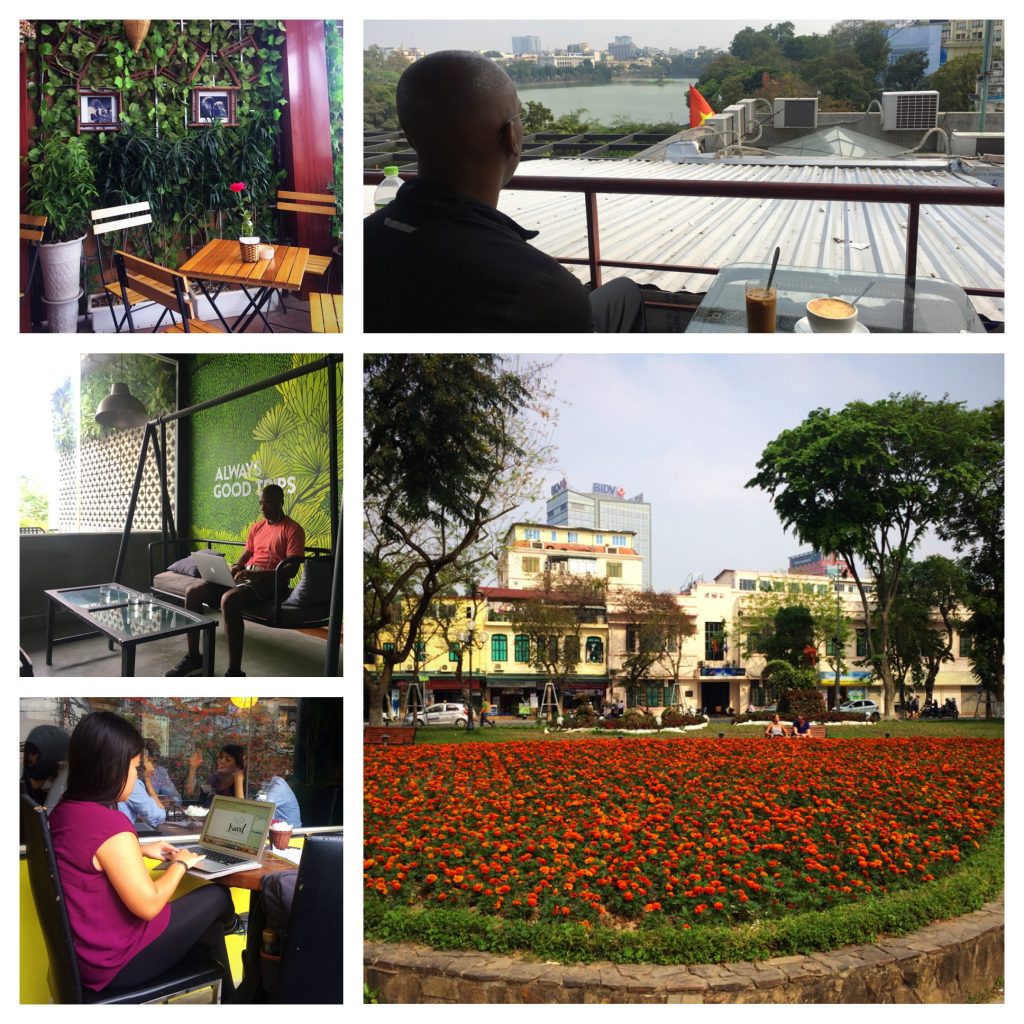

Hanoi is dramatically more scenic, calm, and picturesque than Saigon. The lakes, the parks, the grand boulevards (both French-inspired and Stalinist), and the colonial architecture are truly calming and inspiring. Yes, it’s true that walking in the dead center of Old Town can be just as crazy and chaotic as Saigon.

But once you’re away from that fairly tiny part of town, the city calms and nature takes over the senses. After being unable to escape the noise and heat of Saigon, it was so comforting to spend the afternoon strolling along banks of the lake in the main city park or enjoying an egg coffee from atop a rooftop café overlooking the city and its main lake. Or simply sitting on a sidewalk having a beer and watching the traffic go by.

Hanoi was the place to relax and reset after such a challenging time in Saigon. I would honestly say that if I had to pick between the two destinations for a new traveler to Vietnam, I’d say visit Hanoi first…as you’ll probably appreciate Vietnamese culture and history more. You won’t feel as rushed or overwhelmed. But if you have the time, visit Saigon as well. There’s nothing like it. It overtakes the senses and forces you to appreciate the poetic nature of organized chaos.

Read more Tales from the Nomadic Adventure and find out where we’ll be in the coming months.

2 Comments

DJMoeMoe

April 17, 2017Takes me back to when I visited Vietnam and back when I first moved to the US and was shocked to hear different ways and speeds of speaking American English. Took me a looong time to recognize it and make my own flow.. very enjoyable read my man!

Paula M. Zimlicki

June 18, 2017Hey Jarard, wondered why I no longer saw you on Facebook so I searched for you on the web and found your website. I love reading about your life and your travels and plan to continue to keep up via your blog. I left Stanford in March 2012 and am now based in Houston. Take care!